AI Challenges Humans on Innovation Path to Progress

Brookings Institution hosts talk delving into the ethics of tech-inspired advances and what role humans play in the future.

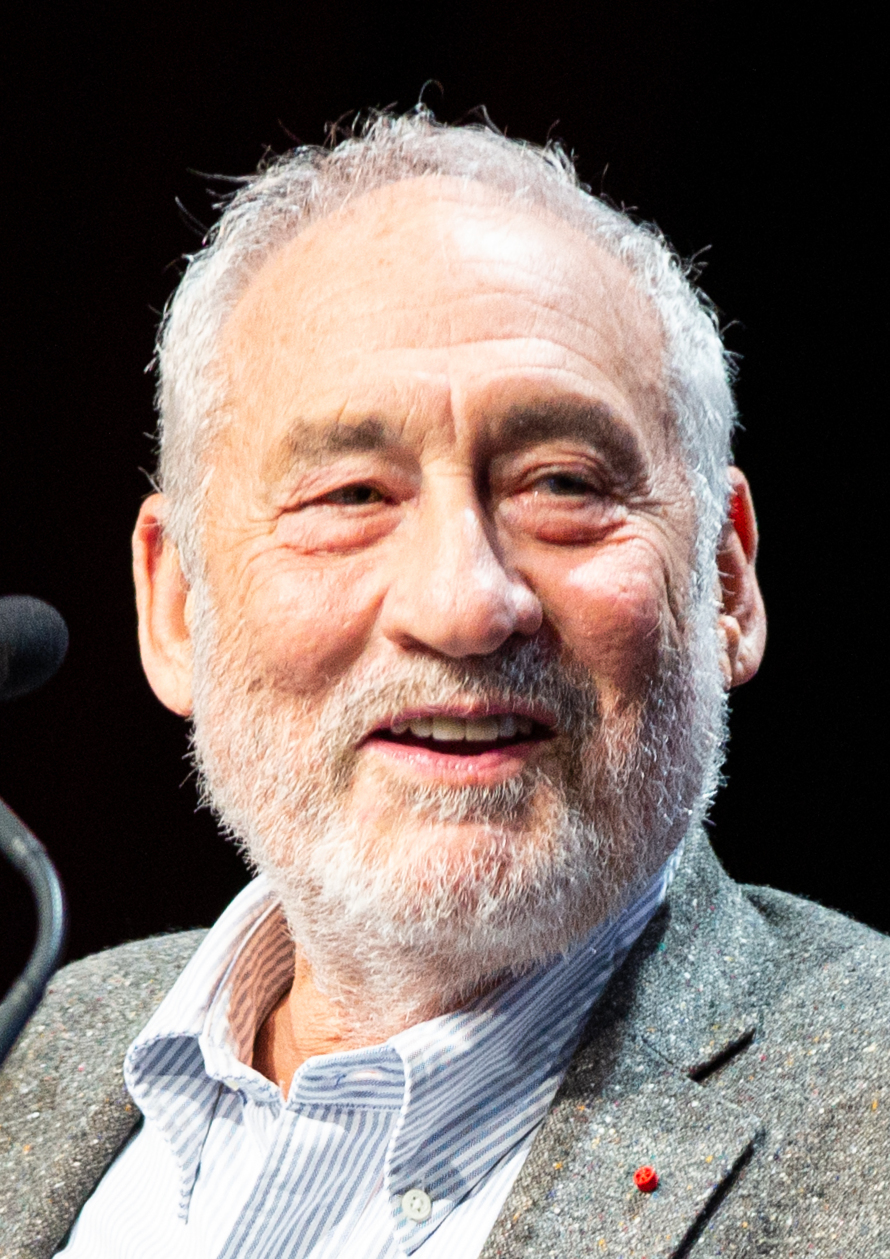

The ability to learn, combined with an ability to process and store information, has given humanity the chance to solve problems that were inconceivable even in the past, according to Joseph Stiglitz, who addressed the pros and cons of AI application in today’s society. Image courtesy of Pixabay.

April 12, 2022

The Brookings Institution, in early March, hosted a brief webinar conversation with Joseph Stiglitz, professor at Columbia University, and chief economist at the Roosevelt Institute. The talk, “AI, Innovation, and Welfare: A Conversation with Joseph E. Stiglitz” focused on up and coming technologies and how they play into intensified social welfare issues. Stiglitz addressed the ups and downs of such innovations and how to make sure that these advances lead to increased value and enhanced social welfare.

Anton Korinek, David M. Rubenstein fellow at the Center on Regulation and Markets at Brookings, moderated the talk. The interaction explored what categories of innovation to steer clear of, how to drive tech advancements in the best societal direction, and how to build a regulatory approach that carries out these plans.

Stiglitz, who is also a recipient of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Economics and a former chief economist of the World Bank and chairman of the U.S. Council of Economic Advisors, opened the discussion with a look back: “… over the past 250 years we've had amazing technological progress. Science, the enlightenment institutions have led to higher standards of living, increased longevity. And yet—and yet, there is not the kind of support that you would have thought for what I sometimes [call] the enlightenment values, the enlightenment institutions, the science, universities, the mechanisms of social, political, and economic organization, rule of law, democracy, separation of powers––a whole set of ideas that we have developed that enable us to cooperate together.”

He suggests part of the reason for the disparity is that the benefits of technology are not equally shared, though the whole of society has benefited in part.

“Our standard of living, [for] even the people at the bottom is so much better [today]. So everybody has benefitted. But some have benefitted so much more than others and this is contrary to the way the economists typically look at things. So even if everybody has benefitted, if some have benefitted a lot more, the people at the bottom still see themselves as struggling because what they think of as acceptable has moved up with success of our society,” Stiglitz explains.

Progress—It’s Not All Good

Whenever there is a change in technology, it may affect the balance of market forces, according to Stiglitz, changing supply and demand curves.

“In a competitive market it just changes market prices. That means that it is possible that some groups in the market equilibrium will be actually worse off. So while the pie is bigger, some groups will get so much smaller a slice of that bigger pie that they're actually worse off,” he explains.

“It's not always the case that innovations make society better off,” Stiglitz notes.

AI Optimism

Stiglitz addresses artificial intelligence, viewing it as the “third step in the innovation revolution.”

First came the development of machines stronger than humans that were capable of handling things physically that humans couldn't do. For example, “we would talk about a car having so much horsepower, let alone human power.” “And then—in the middle of the last century, we discovered that we … made innovations that could compute faster, can do calculations faster. We could add [as humans], but they could add a lot more—faster than we could.”

“But AI does something that we didn't originally think that a machine could do better––it could learn faster [and] learn within a well-defined area. …[but] we have to be able to train it. It can learn how to play games like Go, but [also] actually solve lots of very difficult things that would take us years and years—maybe decades—to learn,” Stiglitz says.

So the ability to learn, combined with an ability to process and store information, has given humanity the chance to solve problems that were inconceivable even in the past, according to Stiglitz.

That said, AI has a significant presence in many areas of science. “The speed of AI may be particularly relevant as we enter a world in which changes occur more rapidly, partly because of technological change. But there is an interesting dynamic here: AI causes faster change and we need AI then to cope with the faster change that AI is in fact causing,” he says.

Downside of AI

It’s no secret that increased use of AI can lead to less need for humans, and Stiglitz affirms such concerns. “Innovation, AI, can lead to a decrease in the well-being of workers, especially unskilled workers, workers whose jobs are more routine, because AI and robotization more generally has the effect of replacing workers.”

Speaking from an economist’s background, Stiglitz explains AI use in a supply/demand frame. “We can create artificially more humans, or more machines that act like humans. And in that way we increase the supply of human-like services and that would diminish the relative return of humans and at least lower their relative position in our society.”

The dilemma goes deeper, according to Stiglitz. “[AI/innovation] even further weakens the bargaining power of workers because now workers have to compete against machines. Machines don't join unions, they don't give you trouble, they don't go on strike. They do sometimes break down, but they don't get COVID-19.”

In such cases where AI is replacing human labor this resembles a concept that Stiglitz references by John R. Hicks, called labor-saving innovation.

Such an issue impacts workers’ bargaining power, especially human workers for whom AI would be a viable alternative.

“And that creates greater inequality and greater inequality has all kinds of societal consequences,” Stiglitz says.

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

About the Author

Stephanie is the Associate Editor of Digital Engineering.

Follow DE