Desktop vs. Mobile Dilemma

Sorting out individual workstation benefits boils down to how the engineer plans to use the system.

Precision 5470 is a thin-and-light mobile workstation suitable for a wide variety of tasks where mobility is more important than power. Image courtesy of Dell.

Latest News

February 9, 2024

For most engineers, it has been years since choosing a mobile workstation meant compromising on performance. With every graphics processing unit (GPU) and CPU product cycle, Intel, AMD and NVIDIA routinely release desk and mobile versions of most products. Only those who need top-of-the-line performance for the most complex simulations and visualizations will be forced to limit their search to deskbound workstations.

Yet the two workstation types do have their differences. Buy a deskbound workstation and there will be no lack of I/O options or wattage. A mobile must make trade-offs to achieve weight and battery requirements.

The fundamental distinction then, is not about the hardware itself, but about how the buyer will use it. Workflow is the key. “It always comes back to workflow,” says Allen Bourgoyne, product manager at NVIDIA. “What do you do? How do you do it?”

“Physics can’t always be overcome; there are thermal limitations in mobile [workstations],” says Brooks Flynn, director of desktop and mobile product development at Lenovo.

For some, Flynn adds, there is also an aesthetic consideration. “There is a sense of the ‘designer workstation,’ a defined workstation and setting. Some users have decided they don’t want to be mobile and go work in the kitchen” even if it is an option.

Over the years, the value equation has flipped; now, generally speaking, the software an engineer or designer uses is more expensive than the hardware. This sometimes makes for confused buying decisions. At the workstation purchase level, it is much more common for the vendor to work closely with the end user or the department purchaser.

“Customers don’t always know what they want,” says Flynn. “If they can give us a dataset to text with various configurations, we can fine-tune the recommendations. Sometimes they don’t need the top of the line.”

Fast Not Efficient

CPU vendors continually work to improve performance per watt, not only for product value but also to be good (green) corporate citizens. For workstation computers, the goal is performance. A CPU/graphics processing unit (GPU) combo might consume one-third more electricity but finish a task in half the time of a wattage value option.

“Vendors must invest in cooling, in air flow and to do so they have to sacrifice battery life,” says Josh Covington, marketing director at Velocity Micro. “You can’t just upgrade the CPU of an existing enterprise notebook computer and call it a mobile workstation. These processors are designed to be fast, not efficient.” The supporting components must reflect the difference.

Such trade-offs are important considerations in the desk vs. mobile decision process. It gets more complicated with the intended workflow.

The market for engineering workstations is competitive at the mainstream (entry) level for CPUs and GPUs between Intel/AMD (CPUs) and NVIDIA/AMD (GPUs). Much of the use is 2D and 3D mainstream CAD, which relies on single-threaded processing. The Intel Core series is the heavyweight in this category, but AMD Ryzen CPUs are increasingly seen as a suitable alternative. Beyond that, the higher performance markets are heavily skewed toward the Intel/NVIDIA duopoly. For mobiles, the entry-level workstation market reflects the larger enterprise market, with Intel/NVIDIA getting the lion’s share.

AMD is seeing nice growth in the entry level and beyond with its new Threadripper and Threadripper Pro high-performance lines. This CPU family is single-threaded but packs more cores and threads into the CPU than competing CPUs from Intel. One example is the BOXX T4 Pro, which runs an AMD Ryzen Threadripper Pro with up to 96 cores/192 threads. BOXX says the differences between the two AMD CPU lines are value per core (Threadripper) or GPU-intensive and/or memory bandwidth-dependent applications (Threadripper Pro).

Unintended Benefits

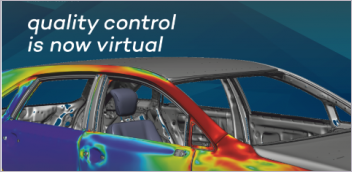

Because NVIDIA GPUs are now used beyond purely graphics-based applications (primarily artificial intelligence), the company is as driven as ever to provide greater performance with each new generation. Sometimes that leads to unintended benefits.

The current generation of NVIDIA GPUs is named Ada; the previous one was Ampere. The Ampere RTX A4000 had a max power consumption rate of 140W; the equivalent model in the newer Ada generation was able to drop this to 130W. For deskbound computing, the Ada RTX line has more powerful options up to the RTX 5000. It doubles the compute unified device architecture (CUDA) parallel processing cores (from 6,144 to 12,800) and raises GPU memory from 20GB to 32GB, resulting in a whopping 250W max power consumption. The ADA-generation equivalent to the RTX 5000 cuts back the cores to 9,728 cores.

AMD’s Threadripper Pro CPUs, particularly the Ryzen Threadripper Pro 5000 WX-Series, are exclusively used in desktop-based workstations rather than in mobile workstations. These processors are known for their high performance, supporting up to 64 cores and 128 threads, making them an excellent choice for demanding applications in engineering, research and content creation. Other models in the WX series offer up to 96 cores and 128 lanes of PCIe 5.0 connectivity.

HP is one of several vendors offering Threadripper technology as a deskbound workstation option. The Z6 G5 A uses the Threadripper Pro 7000 series to support various configurations and specifications all the way up to 1TB of memory. Like other vendors offering AMD Threadripper, there is no mobile equivalent.

Power consumption is the big reason Threadrippers are not used in mobile workstations. For example, Threadripper Pro 3995WX has a thermal design power (TDP) rating of 280W, significantly higher than typical mobile CPUs. The design solutions to cope with such high wattage in a mobile chassis are just not practical.

Today’s State of the Market

Most full-line computer vendors and several boutique companies offer at least one mobile workstation. From the hundreds of potential configurations available, here are three to showcase variations now on the market. Each one below can be customized in many ways, so specs such as RAM and screen resolution are suggestions.

Lenovo ThinkPad P16 Gen 1 bridges the gap between a high-performance enterprise laptop and more powerful mobile workstations. It uses an Intel Core i9 CPU supported by 64GB RAM and the NVIDIA RTX A5500 (Ada generation) with 16GB of memory. Native screen resolution is 2840 by 2400 on a 16-in. screen. Noticeable by their absence are touchscreen capabilities and an ethernet port. It weighs 6.4 lbs. and has a factory-rated battery life of 7 hours and 44 minutes.

MSI CreatorPro X17-A12U cuts no corners. It may be too heavy for routine portability (6.8 lbs). It uses the same CPU/GPU combo as the Lenovo above, but is distinguished by a 17.3-in. 4K display (ultra high-definition) using True Pixel technology. The retro stylish RGB keyboard will appeal to the engineer aesthetic. Native screen resolution is 3840 by 2160. Unlike many current mobile workstations, there are an abundance of ports, including ethernet. Battery life is rated at 6 hours 29 minutes.

Dell Precision 5470 stands out in the crowded thin-and-light segment of the mobile workstation market. It weighs a svelte 2 lbs. and has a factory-rated battery life of 14 hours and 47 minutes. To keep the weight off, this model requires an adapter for most external ports. The Intel Core i9 CPU is supported by the NVIDIA RTX A1000, with 4GB memory. Native display resolution is 2560 by 1600. The touchscreen is a nice plus.

More AMD Coverage

More Intel Coverage

More Lenovo Coverage

More MSI Coverage

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Randall S. Newton is principal analyst at Consilia Vektor, covering engineering technology. He has been part of the computer graphics industry in a variety of roles since 1985.

Follow DE