Printing and Pest Management

Florida Department of Agriculture uses 3D printing to build a better bug trap.

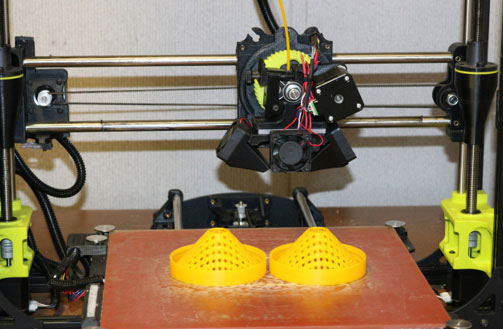

Though intended for prototyping work, Snyder also uses his small fleet of 3D printers to manufacture parts by the tens or hundreds. All images courtesy of Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Latest News

April 1, 2021

A forester with the Tennessee Department of Agriculture says gypsy moths represent a significant threat to the state’s forests (bit.ly/3uvuQUv). A Pennsylvania State University study estimates that the spotted lanternfly could cost the state’s agricultural industry $324 million a year and thousands of jobs (bit.ly/3dFx2D7). The Dallas Environment and Sustainability Committee met recently to discuss the emerald ash borer, which has destroyed millions of ash trees throughout the United States and now has set its sights on Texas (bit.ly/2NVabIQ).

Invasive species like these are everywhere. Some are from Asia, others from Europe, but all have at least two traits in common. First, they don’t belong here in the United States, and second, they’re killing trees, crops, insects—and in the case of the Asian tiger mosquito—humans (bit.ly/3kiXsMj).

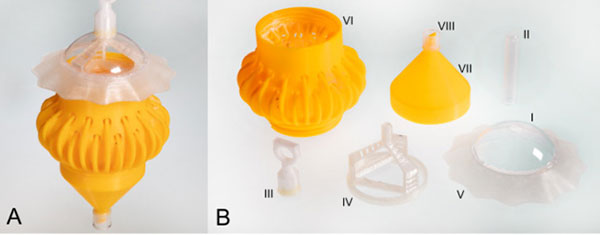

James Snyder and his colleagues at the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services know all about such pests. In fact, they spend their days developing better ways to trap and hopefully control insects like the corn earworm and the Asian citrus psyllid, two invasive species that wreak havoc on the state’s agricultural industry.

Over the past few years, however, they’ve latched onto a manufacturing methodology that’s making their job easier, faster and more cost-effective: 3D printing. When used in conjunction with modern design software and virtual reality tools, it is poised to turn this vital sector of the entomological sciences on its head.

Building a Department

Snyder is a technician at the Division of Plant Industry’s 3D printing lab, part of the state’s Bureau of Methods Development and Biological Control in Gainesville, FL. He began working in the lab in 2017. It wasn’t his idea to print bug traps—that was the brainchild of lead hemipterist (one who studies cicadas, aphids and other organisms of the genus Hemiptera) Susan Halbert two years earlier.

Given the endless parade of additive manufacturing success stories over the past few years, some might think, “The guy’s 3D printing high-tech bug motels. So what?” And while that viewpoint is understandable, what’s most interesting is the significant progress that Snyder and the others in the department have made, given the state’s relatively small investment in 3D printers.

There are no hugely expensive laser-based industrial selective laser sintering machines here, nor equally costly design software. Using products within the financial reach of even a moderately serious hobbyist, Snyder can quickly prototype whatever bug trap design he’s currently dreaming up, then print tens or even hundreds of them for field testing.

“We study an insect’s behavior, its biology, environment and interactions with other insects, then figure out how to most effectively trap them,” he says. “This might involve using different color materials, for example, or creating part geometries that encourage the insect to travel down a funnel. Many of these shapes would be extremely expensive or outright impossible to make using traditional manufacturing technologies like plastic injection molding.”

Frugal but Effective

Snyder has a handful of low-cost 3D printers at his disposal. All use fused filament fabrication (FFF) technology, and all are easy enough to use that Snyder has been able to “pretty much pick it up on my own.”

These include a LulzBot TAZ 5 and TAZ 6, a Tiertime UP BOX+ and UP mini 2, and his largest machines, a pair of Replicator Z18s from Makerbot and a Version 1 German RepRap X400. Most of his projects are made out of polylactic acid, although depending on the printer, he can also print acrylonitrile butadiene styrene, Nylon, polyethylene terephthalate glycol and other polymers.

He also uses Rhino design and modeling software, which he says is more than adequate to his needs, even for the meshes and other complex shapes common with 3D-printed parts. Once he deems a design ready for printing, he exports the .STL file to whatever printer he’s using for that project, then uses the software that came with the machine to ready the file for printing.

“I can design and manufacture most any geometry imaginable,” says Snyder. “At some point, we’ll have some of these products injection molded, but for now, we’re focused on finding the best design possible without spending a bunch of money on tooling and outside services.”

Bug’s Eye View

Unless born with wings and antennae, how does anyone know what might be attractive to an insect? Here again, Snyder has taken an unorthodox approach to pest control by donning a virtual reality (VR) headset and “flying” into and around 3D models of his trap designs. This allows him to analyze light levels, material colors and small details that might otherwise go unnoticed by all but his intended targets: invasive species.

“The most important thing is to learn the insect’s behavior,” he says. “Most of it is basic stuff like what time of the day or night are they most active? Do they have good eyesight? Do they prefer certain colors and specific shapes? Do they hang out in the trees, or around the ground? There are all sorts of questions about how these invasive species interact with their environment, and 3D printing helps us answer them. It’s a lot of fun.”

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Kip Hanson writes about all things manufacturing. You can reach him at .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address).

Follow DE