Digital Engineering’s Pivotal Moment

In efforts to combat COVID-19, many solutions are being developed by engineers collaborating with other engineers and scientists.

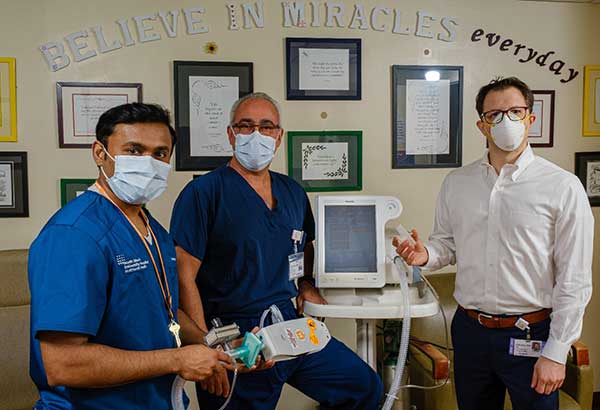

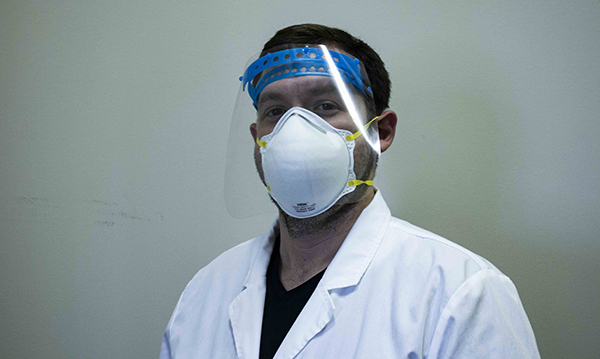

Manufacturing has proved its rapid ability by a digital collaboration, behind the scenes, whereby additive manufacturers support subassembly and assembly manufacturers, to ultimately be fitted into ventilators that save lives. Image courtesy of Northwell.

Latest News

April 27, 2020

In Morrisville, NC, an additive manufacturer works diligently to fabricate parts used ventilators manufactured by General Motors. In New Hyde Park, NY, a physician, respiratory therapist and 3D printing bioengineer collaborated to convert a bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) machine into a functional invasive mechanical ventilator using adaptation produced by a design and 3D printing. And in Chicago, a 3D printing firm is employing “high-area rapid printing” (HARP) to fabricate medical face shields for health care workers at a rate of 1,000-per-day, per-printer, to help protect essential workers against COVID-19.

Such efforts represent just a few faces in the crowd of engineers working with other engineers and scientists to collaborate and develop solutions. If anything is to be learned from the coronavirus strike, it is that public policy and executive decisions are important, but in the end, science and engineering has played, and will continue to play, a great role in finding interim and long-term solutions to a long term, widespread and destructive problem.

“Coronavirus is taking the lives of citizens and healthcare workers in the U.S. and countries around the globe, as hospitals face a shortage of healthcare equipment. We have a technology that allows us to manufacture products quickly, especially in a time of crisis,” says David Walker, CTO and co-founder of Azul 3D, a 3D printing company.

“Our technology is like nothing else in the marketplace and we’re committed to using it for this essential cause,” Walker adds. “By rapidly printing face shields and potentially other critical components, we’re ready to take on this fight to slow the impact of coronavirus. We have an opportunity to assist our health care workers as they face unprecedented challenges, by taking advantage of our great team and the technology we have developed.”

The supply of equipment and supplies was never prepared for the magnitude of demand that has surfaced as a result of the pandemic infusing the world over. Personal protective equipment (PPE) is required by anyone near the virus. Masks, face shields, goggles and protective clothing are needed in quantity and volume to supply frontline professionals.

PPE and other parts and supply, however, can’t wait for normal manufacturing at scale, with routine delivery. Suddenly the need for parts, supplies and equipment is immediate. Its absence is potentially life-threatening. As such, firms able to contribute are rising to help with the same speed as the surge in demand for such goods.

Protolabs headquartered in Maple Plain, MN, fabricated parts in their additive manufacturing facility located in Morrisville, NC, for Ventec, a partner of General Motors, in the production of ventilators as part of the national effort to provide sufficient ventilators for hospitals across the nation.

“Protolabs is prioritizing COVID-19 related parts and waiving expedite fees on any orders during this critical time,” explains Rachel Hunt, 3D printing marketing manager, for Protolabs. “We have fulfilled orders for health care providers, medical device manufacturers, diagnostic equipment manufacturers and design firms all needing 3D printing prototyping and production parts that support PPE, test kits, ventilators and even fixtures for manufacturing lines building COVID-19 critical assemblies.”

Collaborative Progress

Northwell Health, a large health care provider in New York State operates some 23 hospitals and an additional 750 outpatient facilities. Its 13,600 affiliated physicians are busy at work in state that has called the epicenter of the virus in the U.S.

Members of their staff collaborated to transform a BiPAP machine into a defect ventilator should health care workers be left with no other viable alternative. BiPAP is a type of PAP, or positive airway pressure, non-invasive machine commonly used to instill a more consistent breathing pattern at times. It is often used by those with sleep apnea, at night or during symptom flare-ups in people with sleep apnea, congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Hugh Casseire, M.D., medical director for respiratory therapy services at North Shore University Hospital (NSUH)—a hospital within the health network—and Stanley John, NSUH’s director of respiratory therapy, led a team to develop a means of converting the non-invasive Philips Respironics V60 BiPAP machine into a pressure-controlled ventilator for patients with and without COVID-19 induced lung disease.

“Our hospitals are at the U.S. epicenter of the coronavirus epidemic, and some of our COVID-19 patients require intensive care unit therapy and mechanical ventilators within minutes of being hospitalized,” says Dr. Casseire. One sleepless night, Dr. Casseire thought of the fleet of unused BiPAP machines in the hospitals. “I knew we could develop a way to repurpose and convert these machines to save hundreds of lives,” he says.

A small, plastic T-piece adapter is a key component to convert the BiPAP machine. Northwell has a 3D Design and Innovation department. Casseire’s team collaborated with this department to rapidly design and 3D print the T-piece in days.

“We were able to imitate the design of the T-piece adapter and print the plastic-resin piece with our 3D printers,” says Todd Goldstein, Ph.D., director of Northwell’s 3D Design and Innovation department. “If the need arises, we would be able to print 150 adaptors in 24 hours.”

Protolabs operates as a digital manufacturer and works with manufacturers to prototype or fabricate qualified production designs. Their expertise provides a means of automating and designing for manufacture via 3D printing, depending on design constraints.

Collaboration in engineering has come to the forefront to make the supply chain near immediate at a time where fabricated parts displace the normal lead time for any parts required to create complex machines such as ventilators. Image courtesy of Ventec.

In this case, engineered plastics material was suitable to help their customer, Ventec, a partner of General Motors. “Most of the COVID-19 related time critical orders we have seen are heavily reliant on plastic 3D printing materials like thermoset stereolithography resins or sintered powdered nylons,” says Hunt. “Engineers should understand how the technologies produce parts so they can design for additive manufacturability specific to their plastic of choice. It is also important to note that manufacturers should follow guidance from applicable regulatory bodies to ensure designs are safe and effective at fighting this pandemic.”

Protolabs exemplifies the willingness of fabricators to act with agility and roll up their sleeves to get the job done. Others like them have joined in.

Fabricators who were able to contribute could, by registering through a public Google Sheet, set up to gather those who may offer 3D printing services worldwide. Such services can be used to produce materials similar to the ventilator parts used in new manufacture, but also supply replenishment parts such as required oxygen valves for operating equipment. The Google Sheet was a version of manufacturing-as-a-service (MaaS), whereby a demand order may be fulfilled through a central repository by those with capacity and qualifications to fabricate such components, parts or other materials.

A similar initiative was organized by Formlabs, a 3D printing firm. The company established a support network whereby available manufacturers could respond to projects in need of someone to produce them. They did this through a simple Twitter post, offering to connect capacity and supply with the subsequent demand.

Working 24/7 to Meet Demand

Azul 3D developed its HARP 3D printing technique last year. They use a 3D printer that is 13 feet high on a base of a 2.5-foot square base. They’re able to create material at the rate of half a yard per hour, which is productive for a printer of this scale. It was put to the test as the coronavirus emerged and the company and their printer is able to reach sufficient production rates and is ready to reach a rate of 20,000 shields per week within the next few months.

“Even fleets of 3D printers are having difficulty meeting demand for face shields because the need is so enormous,” says Chad Mirkin, chairman, Azul 3D. “But HARP is so fast and powerful that we can put a meaningful dent in that demand.”

Also contributing to the surge in demand for face shields is Stratasys, who makes 3D printers and has a robust network of partners who all pitched in to donate capacity across the United States to fabricate thousands of disposable face shields for use by medical personnel.

Engineers, students, doctors and manufacturers join hands remarkably well in times of crisis. They demonstrate their ability to multiply the power of knowledge and ingenuity when bringing innovation forward, in record time.

Stratasys CEO Yoav Zeif may have stated it best, by stating his own firm’s posture to use the technological intellect of 3D printing and the many who help turn raw feedstock into useful goods ultimately help save lives.

“The strengths of 3D printing—be anywhere, print virtually anything, adapt on the fly—make it a capability for helping address shortages of parts related to shields, masks and ventilators, among other things,” says Zeif. “Our workforce and partners are prepared to work around the clock to meet the need for 3D printers, materials, including biocompatible materials, and 3D-printed parts.”

More Formlabs Coverage

More Protolabs Coverage

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

Latest News

About the Author

Jim Romeo is a freelance writer based in Chesapeake, VA. Send e-mail about this article to DE-Editors@digitaleng.news.

Follow DE